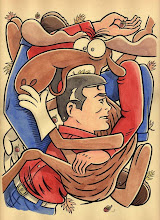

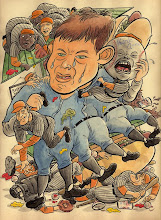

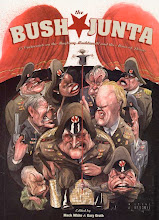

Cosmic Capers, the underground comic that helped send me on my way to a life of juvenile debauchery and infamy.

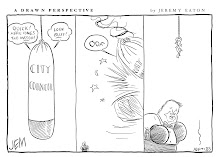

“And the Cub Reporter of the Year award goes to Jeremy Eaton!”

Huh? What?

I blinked, dazed, slumped in my seat like a wilted flower, my mind in a thousand places, not one of which was the drab assembly hall of my high school, that faceless occupation zone of middle American education, situated in the rural humdrum of Western Pennsylvania, some forty-odd miles north of Pittsburgh.

There I sat there, hardly recognizing that my name had just been announced, even as its amplified broadcast rode over the capacity-filled auditorium like some alien cloud, born of a wind that teased at the frayed edges of the freak flag I carried throughout my latter years of supervised learning, those days of early illumination, when I checked out and checked into myself, navigating the path that would lead me to where I find myself today, a modest earner with a wholly individual occupation, a man with enough personal space to see where I end and “it” begins, that mad caterwaul of competing noise and information we call modern civilization.

The mascot of my final school years was an armored medieval knight, more Monty Python than King Arthur, one occupied by a patchwork student body, a strange mash-up of next generation farmers, always red-eyed and yawning from early morning chores – tobacco-chewing hunters, sporting book-sized laminated licenses on the backs of their bright, safety-orange jackets – small town jocks, all vitamin pill pimples and page-boy haircuts – Lynyrd Skynyrd-worshipping “freaks”, with their scruffy “fuck-you” beards and chain wallets – optimally un-cool geeks in their father’s old dress shirts and flood pants (the Bill Gates army, silently ready to storm society with their digital revenge) – and the occasional oddball outcast like myself, we “the unlabelled”, the aloof canvassers of the adolescent periphery.

It wasn’t that I was a nerd. I wasn’t picked on or made fun of, I was simply an ethereal visitor, a mostly-silent witness to the testimony of stupidity I saw before me. More often than not, I found myself grouped with the motley freaks, the long-haired dope smokers and their girlfriends – girls who, at the time, matched my idea of the perfect woman, with their wild, kinky hair and slow, sensual eyes, exhibiting an ease with their physicality that whispered the possibility of situations I could only dream about. When not slouched high in the bleachers amongst this rabble of undesirables, I was keeping uneasy company with the future valedictorians, those uber-geeks of science and language arts, my proclivity to writing and creative thought leading me into advanced classes I always felt out of place in, my hatred for the system at odds with their patriotic upholding of its every armored link.

“Eaton! Get up there, jerko! They just called your name!”

I turned, seeing the gawking faces about me, imploring me to head down the carpeted aisle to the stage, where the school vice principal stood waiting with the award I’d earned for the tepid stories I’d written during my first season with our school newspaper, all toast and cold water in his tweed suit, scanning the crowded room for some sign of a student he’d probably never heard of. It was then that the chant began, slow and soft at first, soon rising, gaining voices, quickly becoming a chorus of freak-fueled bravado, a martial beat that declared “Porn King! Porn King! Porn King!”

Wincing, perhaps more from the assembly recognition than from the scandalous cheers of my unwitting peers, I stumbled towards the front, thankful for the semi-darkness, shyly accepting a piece of paper I would tear into pieces before I even climbed aboard the school bus at the end of the day. It was both my great distaste for the trappings of my pedagogical prison, and the secret shame of personal betrayal, that gave me my awkward hesitancy that early afternoon back in 1978, my queasy guilt forged in the confused, amplified chambers of a fifteen year-old’s troubled psyche. I was, after all, “The Porn King”, just as they claimed, a criminal of the hallway, my standing with respectability lower than that of the buck-toothed old men who ran their grey mops across the piss and chew-stained tiles of our bathroom floors.

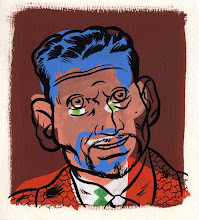

I still remember the cold look in Mr. Tony’s eyes, a look he might well have offered fresh dog shit discovered on the underside of his shoe, a look that said he wanted nothing to do with me, not ever again.

If we had previously enjoyed an adverse relationship, it might have been easier to shake off such rejection, but I had been his chosen one among the forty-odd students that made up the entirety of his art elective class, the rubber cement-scented daycare for underachiever and overachiever alike, sanctuary to greasy-faced, heavy-lidded boys and above-average looking girls, all professing a “genuine” love of the visual arts, most simply searching for another way to escape the regimented drudgery of public school captivity.

What had turned Mr. Tony, my one-time champion, the grey-haired Bob Ross of our school, against me? Just what had set a sizable portion of the freak population to blessing me with my infamous title?

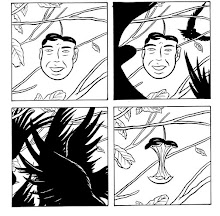

It was Mr. Tony who had unwittingly set me on my course to moral condemnation and ruin, some two weeks before, challenging the class to create their own comic strips.

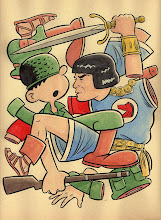

Already being a certified cartoon junkie, I took the challenge like Michelangelo taking to the Sistine Chapel, expanding the simple mission with an acutely secular fervor, to encompass what I intended to be a fully-realized “graphic novel”, a pencil-rendered work starring my space opera hero, Flip Rhodun, who would later go on to infamy in the greater Pittsburgh area, appearing in his own actual daily strip (see “Confessions of a Comic Strip Terrorist” for the full story of that ill-fated venture into mainstream publication). Mr. Tony, immediately sensing my dedication and understanding of the form, took my first finished page (of an epic story concerning a planet of evil, dentistry-related bandits, no less) and posted it in the showcase located at the front lobby of the school, there for all to see, student and visitor alike. I was then charged with the task of creating a new page each week, which he would pin beside the previous, ultimately creating an entire tableau of my graphite masterwork. There I was, overnight having become an instant artist of local renown, a man who could do no wrong with a No. 2 pencil –until that fateful day, the day I stupidly allowed the latest episode of Jack the Ripper Jr. to slip between the working pages of my showcased triumph.

My enthusiasm for the cartooning project having quickly made me the center of attention, my classmates crowded about me as I scrawled away at my amateur efforts. It didn’t take long for the requests to start, for some burnout to demand I draw something “totally wicked”, which translated to something involving sex or violence, preferably both, that sturdy cocktail of our entertainment culture. Enjoying my sudden ability to motivate such a response in others, I capitulated, turning out a series of clandestine strips featuring an adorable little serial killer named Jack the Ripper Jr., the diapered offspring of London’s infamous gaslight stalker. Inspired by the recent acquisition of an underground comic, the first I’d ever seen, I created these crude toss-offs, all involving Jack Jr. and his never-ending battle with the prudes of the world – the teachers, the principals, the police, the scout leaders, the church figures – any authority figure who called for his head in a noose, simply because he’d inherited his father’s unquenchable desire for blood, especially that of a buxom blonde named Dolly, a timely approximation of Dolly Parton, who was regularly being chopped into tiny bits, only to return, whole again, to entice and scorn poor Jack anew. These were generally quite tame, especially compared to the others I gave away, the raunchy commissions that have all but been lost in the wake of my passing memory, ridiculous parodies of popular cartoons, my uninformed updates of the notorious Tijuana Bibles of the 1930s and 40s, those hastily-crafted booklets featuring familiar cartoon icons doing very unfamiliar things. It was these exploitative works that had labeled me a wizard of pornographic art, a fifteen year-old peddler of cartoon smut, The Porn King of “Corn Belt High”.

“What is this?” asked Mr. Tony, flipping through the partially-finished pages of my space fantasy, coming to a short tier of panels depicting Jack the Ripper Jr. telling a man of the cloth to, in no uncertain words, “Fuck off, priest!”

I blanched, sinking into the floor, my short-lived glory suddenly replaced with the uncomfortable burden of a pariah.

“It’s just something else I’m doing,” I replied, my voice fractured with guilt.

Mr. Tony was silent for a long moment. He seemed to linger on the cartoon, as if it were alive, as if he intended to see its heart stop beating before moving on with his own life.

“I don’t want to see any more of this sort of thing in my class,” he finally said, handing back my folder of art, but not before tearing up the offending strip, dropping it into the garbage can beside his desk.

I suppose I was lucky he didn’t kick me right out of his class. Nevertheless, my Flip Rhodun serial disappeared from the lobby later that day, never to return. What went unanswered was the nature of the impetus of my “indelicate trespass” on civility and decency. Was I unearthing some latent need to shock and infuriate – or was my early dabbling with the underground more a reflection of the twisted desire of my captive audience?

I’d encountered my first underground comic book that same year, during the heady, hormonal dizzy spell we call the ninth grade.

Entitled Cosmic Capers, it was a one-shot anthology published by Big Muddy Comics Refinery, the comix imprint based in New Orleans in the early 70s. It was furtively slipped into my gym bag after track practice by, I later discovered, the star runner of our school, a shifty-eyed troublemaker who often held court in the cafeteria, holding in rapture a throng of wide-eyed hayseed dilettantes, dispensing his stories of such then-exotic heralds of the counter-culture as Bob Marley and Frank Zappa, the poets and prophets of a reality that seemed about as far removed from our rural Western Pennsylvanian existence as could be imagined. An Army brat, the speedy messenger was an outsider like myself, but one built on extroverted mettle. He had traveled not just this country’s urban landscape, but ports abroad, making him a literal svengali of the outside world, those heady neon drags of big city life we’d been informed were full of debauched sex, crime, drugs, music, and artists – the playgrounds of bohemian spirit that made our dull little lives seem just about as dull, and as little, as they in fact were.

Cosmic Capers was rather benign, certainly by underground standards. It featured neo-realistic stories by third-tier comix artists like Jim Wright (Jesus Christ vs. Godzilla) and Ned Dameron, their art scratchy approximations of silver age artists like Al Williamson, far from the graphic splendor of pen and ink auteurs like Robert Crumb. The one story that captivated me the most was a hoary science fiction tale featuring an astronaut landing on a seemingly-deserted Venus, only to find a naked hippie girl awaiting him, who quickly entices him into removing his spacesuit. Two awkward panels later her vagina is transforming into a giant Venus flytrap, devouring the horny spaceman in a final, EC-inspired image. The man-eating flower girl tortured me, arousing in my budding libido severely conflicting impulses of lust and fear, so much so that I eventually gave the comic away, but not after keeping it stashed in the back pages of a big Batman book, fearful my parents would discover it amongst my otherwise mostly-tepid comics library.

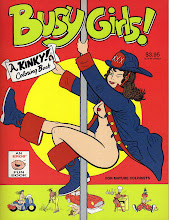

How long after my public shaming I continued producing my own underground-flavored cartoons, I’m not sure, but the strong reactions they generated stuck with me, eventually leading me to investigate the published legacy of comics spelt with an “x”, a journey that would ultimately lead me to my own appearance in alternative comics, which would, in turn, culminate with porn-based titles such as Hump Crazy! and Busy Girls, comics filled with imagery that would surely have made Mr. Tony’s wiry hair unfurl in indignant fury.

I can only wonder what my less-than-respectable high school readership might have made of them. Then again, I think I know.

In fact, I can hear them chanting it right now.

“Porn King! Porn King! Porn King!”

Who? Me?