skip to main |

skip to sidebar

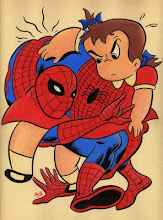

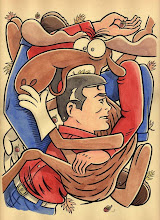

A Mighty Marvel Yuletide Greeting! sang the red italicized lettering, situated within the yellow heart of a Christmas wreath that covered part of The Mighty Thor’s cape. The god of thunder was cast as a reindeer, tethered just behind The Incredible Hulk, who played a green-nosed Rudolph. They were careening across the rooftops of an unspecified city, large snowflakes falling all about them, the sky a midnight blue. Sitting in a green sleigh was The Thing, taking the role of Santa Claus, waving to all the boys and girls, as Spider-Man and Iron Man traversed the periphery. It was one of the Marvel Treasury Editions, a series of tabloid-sized paperbacks that had, since 1974, included an annual holiday collection of seasonal reprints. On the back cover, under a yellow banner that offered an additional “Season’s Greetings”, were assembled Captain America, Giant-Man, The Wasp, The Silver Surfer, Hawkeye, The Black Panther, and The Vision, looking more than ever like a red and green Christmas ornament. Steve Rogers and Hank Pym (the good captain and the giant respectively, to those uninformed), were both smiling broadly, the sort of smiles you find on posters in a dentist’s waiting room. So too was Hawkeye, and the Wasp, held high in Giant-Man's Kong-sized hand, like a seasonally-attired Fay Wray. The alien Surfer and the android Vision were wearing their customarily brooding glares, the holiday spirit clearly not registering in their searching souls. Meanwhile, The Black Panther sat on the edge of a snowy rooftop, his face obscured by his inky black cowl. I can only believe a man driven to sitting during such a celebratory occasion is a man with some holiday-related issues of his own – perhaps one too many pressurized family dinners at the Wakandan homestead?

A Mighty Marvel Yuletide Greeting! sang the red italicized lettering, situated within the yellow heart of a Christmas wreath that covered part of The Mighty Thor’s cape. The god of thunder was cast as a reindeer, tethered just behind The Incredible Hulk, who played a green-nosed Rudolph. They were careening across the rooftops of an unspecified city, large snowflakes falling all about them, the sky a midnight blue. Sitting in a green sleigh was The Thing, taking the role of Santa Claus, waving to all the boys and girls, as Spider-Man and Iron Man traversed the periphery. It was one of the Marvel Treasury Editions, a series of tabloid-sized paperbacks that had, since 1974, included an annual holiday collection of seasonal reprints. On the back cover, under a yellow banner that offered an additional “Season’s Greetings”, were assembled Captain America, Giant-Man, The Wasp, The Silver Surfer, Hawkeye, The Black Panther, and The Vision, looking more than ever like a red and green Christmas ornament. Steve Rogers and Hank Pym (the good captain and the giant respectively, to those uninformed), were both smiling broadly, the sort of smiles you find on posters in a dentist’s waiting room. So too was Hawkeye, and the Wasp, held high in Giant-Man's Kong-sized hand, like a seasonally-attired Fay Wray. The alien Surfer and the android Vision were wearing their customarily brooding glares, the holiday spirit clearly not registering in their searching souls. Meanwhile, The Black Panther sat on the edge of a snowy rooftop, his face obscured by his inky black cowl. I can only believe a man driven to sitting during such a celebratory occasion is a man with some holiday-related issues of his own – perhaps one too many pressurized family dinners at the Wakandan homestead?

This was the publication I was holding onto, that inclement December Saturday in 1976, feeling a strange and horrible guilt, as my father and I drove away from Rishor’s, my favorite newsstand.

Then just thirteen years old, I was a shy and introverted teenager, one under the spell of a keen, if fleeting, interest in the superhero comic book genre. Like other such nerds, I spent inordinate amounts of time obsessively cataloging my personal archive of Marvels, DCs, the occasional Gold Key, even a few Charltons I’d found orphaned in a local hardware store, the top half of their covers roughly torn off, a returns practice I wasn’t privy to. “Why did someone want just the tops?” I’d asked my father, not being able to accept his quick explanation, refusing to acknowledge how patently ridiculous my theory of some top-hording thief was. I would soon become familiar with the distributor system, the following year, when my older brother’s girlfriend would start working behind the counter at Rishor’s. A pretty, blonde cheerleader, straight out of a Riverdale malt shop, she quickly became a distracting element of my weekly trip to the brick-faced storefront, located on one of the snaky arterials that ran west from Main Street, in the city of Butler, a tired little huddle of homes and businesses, located some forty miles due north of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Having pestered my father without cease that stormy late afternoon, imploring him that I was especially situated to judge the drivability of roads unseen, we’d set off one on of my periodical, periodical treks, my hopes high to find the latest issue of Ghost Rider or The Defenders. Little did I know, fidgeting with my seat belt, watching the sky shifting through varying tones of grey, that I would, in a few short moments, encounter something so unimaginably terrifying the memories of it would still trouble me, some thirty-two years later.

It wasn’t our first shared meeting with horror. Only a year earlier, in Northern Quebec, we’d seen the dark shape of a man holding his young son, dying in the flame-filled cab of an over-turned hay truck, an image my mind still carries with it, like some morbidly curious panel in a faded comic book. But even that hadn’t prepared me for what I was about to confront, on a wet, snowy stretch of Route 8, the main road leading into Butler.

I’m not sure if my experiences with death and terror have been ordinary in this respect, in that they feature a quilt of memories, some sections as vivid as the screen of my computer, others as hazy as a long ago dream. I have endured, in the past, moments of physical conflagration where I appear to have momentarily blacked-out (scoring a goal in a soccer championship, extreme anger, an early sexual experience), a condition I now ascribe to a latent epilepsy. I have always assumed the patchwork bed of remembrance of this unfortunate afternoon to be subject to such gaps in recollection, if not complete consciousness. This would account for the wrath-like way I seem to move in these memories, like some ashen, caped ghost, floating from scene of horror to scene of horror, hardly feeling my limbs.

“Stay in the car! Don’t move!” my father had ordered, undoing his seat belt, the car having come to a sickeningly abrupt stop. From the corner of my eye, I watched him open his door and tentatively step out, my attention on the wreckage and debris that now lay only a few feet before us. Sitting there for a long moment, more so out of an inability to move than in heed of the warning, I could feel my heart pounding against the ribbon of nylon strapped across my chest. I was reliving a devastating motion picture, one that had just burned itself, seemingly forever, upon the threshold of my awareness.

Two cars meeting at a right angle, doors bursting open as windows explode, seatbelts flapping about like seaweed in a storm, two bodies jettisoned free, as if the very atmosphere had sucked them out, limbs careening, turning head over heel as they shoot through the air, across a grey sky festooned with sparkling shards of safety glass.

What compelled me to step out of the station wagon and disobey my father’s stern order I don’t know, my fear of being alone, or my fear of being left inside a car. By this time he had reached the adjoined vehicles. They sat crushed together, nose-to-nose, like brash lovers kissing in a doorway. I had watched him walk out into the center of the two-lane roadway, where a dark brown shape lay across the yellow line, so near I can still see the silver buckle on the man’s boot. It was the driver of the car on the right, the one that had suddenly pulled out of the gas station ahead us, directly into the oncoming vehicle. Whichever one of the two crossed the middle of the road I’ll never know, suffice to say there was a meeting of great speed with sudden obstruction, resulting in grievous harm, doing to the fallen driver something so unappealing it made my father, after stopping and leaning over the body, practically run on to the smoldering cars. It was this thought that gripped me, the moment before my senses must have gone numb, a curiosity born of the primal fear that had descended upon me like the heavy winter sky. On my spectral heels I floated, drawn to the crumpled body, set on its side like a sleeping dog. I can see the brown corduroy coat and the black leather boots, the dirty white fleece of the man’s collar, beside which rested a major portion of his head. The rest, a piece about the size of a grapefruit, hair attached, lay some fifteen feet away. I can’t see the blood involved. That aspect of the grisly scene apparently went right through the gaping maw of my disbelieving mind.

Fleeing the overwhelming presence of death, I found myself moving towards the wreckage, where my father was busy removing the keys from the ignition of the empty car. As I came upon the second, I could see its driver still sitting, his neck slung to one side, as if it were broken. I then noticed the passenger of the first, his back to me, sitting on the wet road, his head between his legs, his palms slapping at the ground, making a strange cooing sound. As I took a few steps forward, he suddenly sat up, beginning to fall towards me. The rear of his head was a wild mass of black corkscrews, the untidy afro of a white man in his late twenties, wearing a plaid hunting jacket and flared blue jeans. Without thinking, I held out my hands and caught him about the shoulders, steadying him the best I could. He was like a bottom-weighted punching toy, wavering to and fro. I don’t know just how long I knelt there, staring into the thick nest of his hair, before the dark blood began to bubble up, a helter-skelter fountain that ran onto his jacket, warm as soup about my cold fingers. Just then I felt a firm hand upon my wrist, followed by a soft voice in my ear, telling me everything was going to be okay. I turned to see my school bus driver, a middle-aged woman with a motherly face. She took me in her arms and escorted me to the side of the road, where I began to notice other people, my father included, moving around the side of a school bus, as police sirens descended upon the scene.

When we finally got back into our car and strapped ourselves in, I was afraid to meet my father’s eyes. I was still numb. “We have to turn around,” he said, in a thin, distant voice, as if he were on the opposite side of very thick door.

“Can we – can’t we maybe, maybe still go to Rishor’s?” I asked, my voice no more than a squeak.

“I really don’t think I can drive through Butler, Jem.”

“Please, dad, please. You can do it – it’s not very far. Please! I won’t be a minute inside – I just want to see if any new ones have come in – that’s all.”

I couldn’t help myself. I pestered and pestered him to take me, soon begging the point. It was as if the accident had never happened. He finally relented, driving around the half dozen flashing police cars that were assembled before a roadblock of burning flares. One of the officers gave us a solemn smile, waving us by. I think he was the one my father had spoken to, giving out his account of the accident.

Only when I was alone inside the newsstand did I begin to feel the horrible guilt. As my eyes ran feverishly up and down the two spinning racks that provided the great majority of my weekly comics fix, it followed me, like the cold eyes of an accusing angel. Finding nothing new to buy, fighting the growing sickness in my stomach, my gaze drifted to the magazine rack where, among titles like Heavy Metal and Fangoria, I saw the brightly-colored tabloid comic, Giant Superhero Holiday Grab-Bag, its festive cover imploring me. I knew it was just a selection of over-sized reprints, but I suddenly wanted it. Grabbing it, I dug into my pocket for the small fold of dollar bills that constituted my comic allowance. As I did, I looked up, seeing my father on the other side of the rack, reading a magazine, grinning at me, like some sad clown lost in a tragedy. He’d followed me in, a thing he rarely ever did.

“Did you get anything good?”

“No, just this,” I sheepishly replied, lifting the tabloid to show it more clearly, as we pulled way from Rishor’s, the outside of my window thick with condensation, making the buildings of Butler look as if they were lying under ice.

My father didn’t reply. Regarding the comic with a weak smile, both hands tight on the steering wheel, he turned back to the road, his eyes glistening.

“I’m sorry it happened,” I managed, almost too quiet to hear, my eyes glued to the gaudy holiday fantasy sitting on my lap, wanting things to feel normal again. It was the last thing either of us said, the entire rest of the way home.

The accident wasn’t even mentioned that night at dinner, even though I knew my parents had already discussed it, in hushed tones, as I sat in the next room, thumbing through the latest addition to my collection. Nothing was said about it the next day either, or the next.

And not a word of it has been uttered between my father and I since, not all the days, and years, gone by.

I’d just ordered a glass of orange juice and a plate of hash browns in a well-worn diner at the top of a long hill, a five block walk from the third story room I rented above an old family-run print shop with an imposing brass door worthy of a story by Dickens. It was a wet, cold, early winter morning. Not yet six o’clock, the grey sky lay like a lid over the stretch of historic brick townhouses that climbed Liberty Avenue, a commercial/residential gauntlet that formed the main arterial of the Bloomfield neighborhood, in the city of Pittsburgh. The year was 1987.

I’d just ordered a glass of orange juice and a plate of hash browns in a well-worn diner at the top of a long hill, a five block walk from the third story room I rented above an old family-run print shop with an imposing brass door worthy of a story by Dickens. It was a wet, cold, early winter morning. Not yet six o’clock, the grey sky lay like a lid over the stretch of historic brick townhouses that climbed Liberty Avenue, a commercial/residential gauntlet that formed the main arterial of the Bloomfield neighborhood, in the city of Pittsburgh. The year was 1987.

Being awake at such an early hour was unusual enough, having had the wherewithal to position myself at the cracked counter of such a sleepy eating place was unprecedented. I was a late riser, accustomed to wolfing down a frenzied breakfast at home before jumping on my bicycle to race perilously down Liberty into the heart of the city, to the editorial offices of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, the city’s long-standing morning paper. My near-miraculous awakening had been spurred by the advent of my latest entry into the editorial pages of the respected daily.

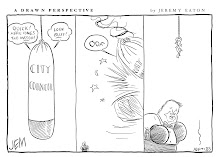

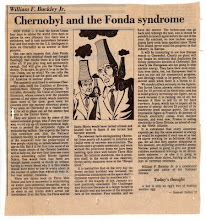

Having been hired, at the ripe age of twenty-three, as the paper’s sole staff illustrator, I had only recently begun to appear on the Op-Ed galleys, an invitation which had given life to a budding sense of social awareness. Determined to draw with both my mind and my hands, I took these editorial stabs as monumental forums for expression. In my young, overly-idealistic mind, I saw them as the print stage upon which I would enlighten and bring change to the staid order of the depressed industrial settlement I’d called home for much of the decade.

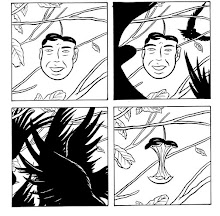

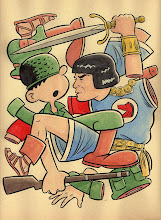

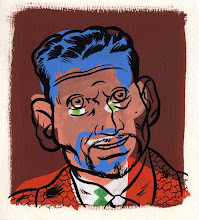

I had raced out of the gate with my very first such piece, a reactive and cynical criticism of the nation’s cattle farmers and their insatiable demand for federal subsidies. It was a hastily-drawn cartoon, a depiction of a cattleman who looked much like the Hee Haw buffoon Junior Samples, bemoaning his lot, as his cattle starved around him in the heat of a summer drought. It promptly attracted numerous letters from angry and offended local farmers. Taking this hostile reaction as a clear validation of my power to influence, I’d practically lunged at the next such assignment handed my way, a cartoon meant to accompany a piece by Michael Kinsley, editor of The New Republic, pointing to the hazy ethical arguments of then- Attorney General Edwin Meese, a man who seemed to feel his actions filtered through an intangible alternate universe where scrutiny was left to wholly subjective devices. Seeking to tackle this potent subject with my naïve pluck, I had made it my mission to challenge the paper’s long-standing readership, the working class men and women who sat about me that dour morning, breathing in their black coffee and eggs, pawing through the pages of the Gazette’s early edition. My obstacle to their routine involved more than a shift in perspective or opinion, it was an actual demand for hands-on participation in my art. It was this tactile adventure that had compelled me to set my alarm for the ungodly hour of five, a time for bakers and street sweepers to be roaming the Earth, not editorial cartoonists.

The interactive hook I’d built my cartoon upon involved optical perspective. Utilizing the old trick of drawing an image in an unnaturally stretched form, I’d rendered my caricature of Meese to run more than three quarters the height of the column. When viewed in the customary fashion it appeared partly out-of-focus, but the caption at the bottom invited the reader to take the paper and hold it so that it was positioned at a right angle to the eye. By doing this, and placing one’s face close to the page, the elongated image would “magically” compress and the identity of the hard-to-pin-down Meese would become clear. Not exactly a groundbreaking premise, but it was nevertheless a concept I had been forced to battle for the previous day, cracking heads with the assistant Op-Ed editor, then the Op-Ed editor, then the editor of the paper himself, before finally finding myself in the cluttered office of the publisher, putting on a cocky show of unearned bravado that seemed to leave each of the previous gentlemen (all old enough to be my father) looking rather bewildered. It was becoming all too apparent that they had hired an illustrator with ambitions far outside the decorative arts (and his own reach). It was an uncompromising desire that would eventually see me packing my things and quitting my post only a few months later, the pathway I’d worn to the publisher’s door having become a trail of increasing frustration and fatigue. But that dreary morning, perched on my counter stool, I was still full of verve, one eye on my greasy breakfast, the other moving about my dozen fellow diners like a hawk, breathlessly anticipating their coming to the editorial page, hoping against hope that they would take my challenge and activate the prescribed action, folding the paper and holding it up to their rough-hewn faces, the steely jaws and ruddy jowls of men and women who I presumed had little time for such artistic conceits.

“Just think about!” I’d declared the evening before, standing in the stately living room of the multi-floored apartment I shared with a photographer and his girlfriend. “I have the power to make everyone in Pittsburgh fold their paper in half and hold it to their face. It could happen all at once. At six in the morning I could make literally thousands of people stop what they’re doing and play my visual game!” I was giddy with the very thought of it, drunk on my own enthusiasm. The afternoon’s victory of will over the paper’s masthead had only heightened my myopic dreams of supremacy. I was a young man who, given an inch, would quickly claim a mile.

“You’re going to leave newsprint on everyone’s cheek,” grinned the girlfriend.

“Exactly!” I beamed, failing to catch the sarcasm in her comment. “I’m like the puppet master, pulling the strings. Isn’t it cool?”

The photographer rolled his eyes. “It hasn’t happened yet. How are you ever going to know, anyway?”

That was the instant I hatched my little plan of clandestine field study. I quickly settled on the most habitual of all the local eating spots, an aluminum-sided bulwark of more than fifty years of service, a multi-generational hash-slinger with roots as deep as the city’s still-smoldering furnaces of iron and steel. Setting my notepad and pen beside my alarm clock that night, I pushed my head into my pillow, my mind full of romantic notions, imagining myself some Diane Fossey of the working class coffee-sipper, my subjects like gorillas in the mist of the cook’s grill.

It was a moment I’d never have anticipated just a few weeks before, finding myself living back home at my parent’s house in rural Butler County, some forty-odd miles north of the city, scraping by on what little freelance illustration work I could find. I was, in fact, standing atop a ladder, painting the eaves of the house, the day the unexpected call came from the assistant editor of the Gazette, letting me know that an opening had suddenly appeared in their graphics department. It was, of course, a happening far more complex, and bound in incidental history, than one surprise phone call. My relationship with the Post-Gazette, and its editorial staff, went back to my earliest days in Pittsburgh, to the reckless pursuit of a neophyte’s search for artistic integrity in a city that shouldered far more practical concerns. This was the Pittsburgh of the Reagan era, a defeated metropolis of industry yet to fully acknowledge it had been fitted for a coffin, a city devoid of any real national cultural identity, a place where a dusty warehouse still occupied the block that would become, almost a decade later, the world-renowned Andy Warhol Museum.

The sad incident that had spurred the phone call was the recent death of the paper’s chief illustrator, a boldly graphic artist whom I had met on my very first visit to the editorial offices, some four years earlier, just a week after I had quit an unhappy and short-lived stint at Pittsburgh’s only commercial art school. Stuffing a series of marker drawings I’d made of the denizens of the city’s pigeon-strewn parks and benches, I’d marched into the bustling newsroom, outfitted in my trademark wool beret and ancient overcoat, commanding the assistant editor’s time, along with most of his desktop. Being a patient and kind-hearted man, he’d heard me out, listening with what seemed genuine interest as I laid out my plan for a Sunday Magazine feature on the city’s street characters, the homeless and aged with whom I mingled every day on my jobless wanderings. Along with copies of my dozen portraits, I presented him with a first-person written narrative of these individuals and the strange world they inhabited. It was a bold move for a failed, nineteen year-old art student with no professional credits to his name. Not surprisingly, the feature was ultimately rejected as being too “narrowly-focused”, but not after it went through the legitimate channels of editorial discussion, the very gauntlet I would regularly face some four years later. Despite this rejection, my debut achieved two invaluable things. One, it gave me a viable contact with an editor, who soon after began offering me freelance editorial illustration assignments. Two, it introduced me to the then-current staff illustrator, the man whose death would create the vacancy I would eventually fill.

This artist, a forward-thinking individual whose work was just beginning to appear in nationally-prominent periodicals like The New York Times and Newsweek, was the very first person I knew who had a computer and who was utilizing the earliest graphic programs to aid his drawing. He, in fact, on our third or fourth meeting at the offices, offered to teach me the program and, to my great surprise, give me license to mimic his style (one centered on traditional woodcuts, infused with the bold cartoon flourish of the likes of early Charles Burns). He was asking me to be his “ghost illustrator”. He claimed this was needed as he was getting too much outside work, but didn’t want to give up his post at the Gazette. Being a victim of a furious pride, I instantly declined, refusing to even consider such an invisible tenure. Little did I know, this was actually a very gracious, and ultimately heartbreaking, offer from a man who had been diagnosed with multiple cancers and given only a limited time to live, a man who had somehow managed to keep these dire health issues secret from the majority of his co-workers. Upon hearing that he had died, images of him, a relatively young man, arriving for one of our lunchtime art chats with a perceptible limp, leaning on a walking stick, raced back into my mind. I later learned that he had suffered a series of operations to remove parts of his infected vital organs, surgeries that had literally caused his body to collapse in upon itself.

Thus, there I was, atop a rickety metal ladder, a paintbrush sticking from my shirt pocket, excitedly agreeing to (unbeknownst to me at the time) fill the shoes of the man who had attempted to steer me in that very direction some two years earlier.

When I was introduced to my desk the following week, and the full tragic story was conveyed to me by the others in the small graphics department, I suddenly felt a weight upon my shoulders, a challenge to live up to not only my own demanding standards, but to honor the kindness of the benefactor I had never truly recognized. I’d like to be able to say that I achieved something of these goals, but my growing frustration working within the rigid structure of such a long-standing daily paper was to get the better of me before I had the opportunity to establish myself in any lasting way. If I managed to forge a recognizable style in those few short months before I quit in frustration, it went unrecognized, even by me, my usual schizophrenic approach to illustration, reacting to each assignment with a different artistic voice, ruling the day. If I did anything, it was to perhaps awaken the editorial hierarchy to the existence of illustrators who desired to achieve more than a fluency of craft, to those who wanted, and needed, to impart an individual worldview in their work. An idealistic notion, to be sure, but one I still stand by.

“Want another refill on this OJ?”

I was startled out of my reverie, finding the middle-aged waitress leaning across the counter, her fingertips at the rim of my empty glass. I quickly nodded I was, keen to return my hopefully unnoticed gaze to the grizzled-looking gentleman in the hunting jacket and earflaps, who had just settled upon the territory of my scrutiny, the morning’s Op-Ed page. He held the section of paper against his lap, a shield behind which rose a steady tower of steam from his unattended coffee. I caught a squint and a furrow come to his brow as he followed the lines of my clandestine illustration, to the bottom, where he brought his eyes closer to the paper in order to read the caption I had created using rub-off prestype. I watched breathless, seeing him roll his shoulders and begin to lower the paper, positioning it as I had intended. I could hardly believe it, he was actually following my instructions, doing something I imagined he had never been asked to do with a morning paper in his life.

It was a moment of victory, one I hadn’t expected to see, for it was almost seven-thirty and I had yet to witness a single reader do more than stare perplexed and move on in silent irritation after encountering my “groundbreaking statement of artistic purpose”. But here he was, the proof of my obvious genius, the blue collar Joe, the no-nonsense vessel into which I would pour my ideas. I straightened my back, rising high against the Formica counter. When the waitress slid my third glass of juice before me I almost declared out loud “Do you see that? That guy’s folding his paper and holding it up to his face! And I made him do it – with art!”

But my elation was short-lived. A moment later, the man was shaking his head in apparent confusion and rustling on to the next page, my monumental achievement pressed again into obscurity between the wrinkled pages of a journal that would soon be mingled with the morning’s coffee filters and cigarette butts, lost at the bottom of a neglected garbage can.

To such events do we ascribe experience, the teeth-cutting to a perspective beyond youthful idealism, the lesson learned of our own insignificance to the greater scheme and unfolding of things, but it is still hard for me to not feel that swelling in my chest, that electric moment when I thought I had conquered the world, when I truly believed the images and ideas generated within my skull could reach out and shape the reality of others, if only in a operatively tactile way. And I suppose that feeling has never quite gone away, not completely, not after all the years between then and now, as I continue to struggle through the mornings, my pen and paper the prime tools of my trade. If I can leave anything of permanence with the work I do, be it the editorial cartoons, the sequential narratives, even the more decorative illustrations I am regularly commissioned to produce, I hope it might be to impart that perseverance is its own reward, that sticking to one’s strengths, no matter how meager the return, is something more than just the foolish bluff of a soul forged through idealism, that it can be the validation of oneself, in a world all too eager to wear that spirit down. I also want to believe that it makes a difference, somewhere, to someone, even those no longer tethered to these unfolding days.Dedicated to the memory and art of Robert Patla.